Both stocks and bonds have been volatile over the course of this year. Throughout this period MoneyLetter’s advice has been to stay calm, stay the course, and if you have investable cash to invest it for the long term. Over the years we have suggested dollar cost averaging your way into the markets, which can be a wise long-term strategy in turbulent times. Given the current uncertainty and market volatility, let’s refresh our knowledge of dollar cost averaging. Alternatively, some of you may be looking to raise some cash – to have a more comfortable amount in an emergency fund or to replenish your retirement cash reserves. With that in mind, we will also look at some considerations for raising cash in the current environment.

Dollar Cost Averaging

The basic premise of dollar cost averaging (DCA) is that set dollar investments are made at regular intervals of time – often monthly, bi-monthly, or quarterly – into mutual funds or other investments. While the amount of money invested in each period remains the same, the number of shares you acquire will differ based on the share prices at the time of the purchases. In most cases, this will end up being to the benefit of the investor. When markets are down, the regular investments will purchase more shares, and when prices are high fewer shares are bought. At the end, the number of shares purchased will most often be greater than if one had made a lump sum investment.

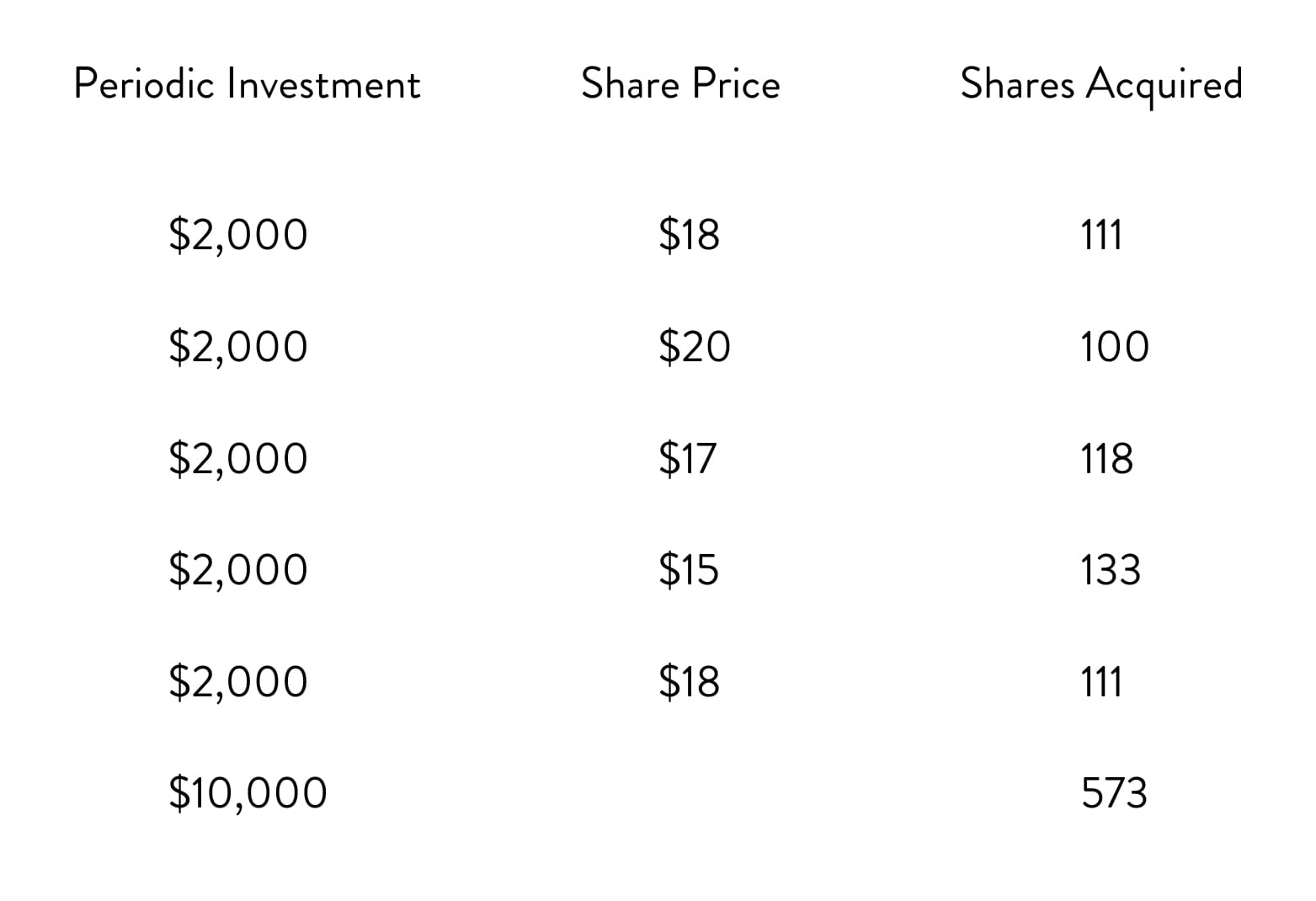

Let’s look at a simple example. Say you have $10,000 ready to go into the markets. You could invest the entire amount on “Day One” or spread that out over a number of time periods. For simplification, we will use five periodic investments (and rounding shares acquired).

More shares for you

A lump sum $10,000 investment in period one would have purchased 556 shares. Utilizing dollar cost averaging, the same $10,000 would have purchased 573 shares, netting an additional 17 shares, and at an average share price of $17.45. That’s quite a benefit, especially when you apply the technique to larger amounts and longer investing periods. This approach is a mechanical approach to the buy side of investing. It removes the emotion from the decision-making process – both on the upside (fear of missing out) and the downside (panic selling when the market is plunging).

Sure, in the hypothetical example above, an investor may have been better off if they had invested a lump sum at a lower price, but there is no way to know when an investment is at a low point, or if it will even decline further. Market timing is generally a losing battle.

DCA for different goals

If you are still in your income earning years, DCA is a disciplined way to build toward a future goal (college educations, retirement, etc.). Alternatively, if you receive a lump sum that you can invest, DCA allows you to ease into the market over time, reducing timing risk. (And if you participate in a 401(k) plan at work that invests directly from your paycheck, you are utilizing DCA even if you don’t realize it!)

No-load mutual funds and ETFs are ideal for this strategy since no commissions are incurred (there may be a small ticket charge if you use a discount brokerage). DCA works best over longer time frames or in times of market volatility. As we know, markets can have prolonged periods of difficulty, but they do advance over the long term.

On the reverse side: Freeing up cash

Things are quite different if you need to free up some cash from your investment portfolio – say to increase your emergency fund in a time of crisis, or to replenish the cash reserves you draw your living expenses from in retirement. At first glance, using a dollar cost averaging strategy to sell investments to provide cash might seem logical, but it is not wise. Reverse dollar cost averaging means you usually sell more shares at lower prices and fewer shares at higher share prices, resulting in a larger portion of your portfolio share holdings being liquidated. That undermines the ability of your portfolio to capitalize on potential future market gains.

Selling a portion of your investments to generate cash needs to be much more strategic. Here are some tactics to consider if you need to raise cash from your investment portfolio. As always, consult with your financial or tax advisor first.

- Rebalance: Look at your overall asset allocation. If a decline in stocks has left you with a higher than desired exposure to bonds or bond funds, consider selling the bonds first.

- Revisit your holdings: You may have investments that no longer fit your strategy. Or long-term holdings whose outlook or qualities have changed for the worse over the years. Those may be sale candidates.

- Harvest tax losses: Do you have securities that are trading at a loss in a taxable account? You could consider selling to raise cash. A loss on the sale of a security can be used to offset up to $3,000 in realized investment gains and/or ordinary income annually.

- Consider short-term versus long-term capital gains: If you must sell assets in taxable accounts for a gain, consider selling those held for more than one year first to take advantage of lower long-term capital gains tax rates (compared to higher short-term or “ordinary income” rates).

By Brian W. Kelly

If you are not currently a subscriber. Click the link below to check out our subscription options.